"... one could

say that this was one of the first teenage

magazines that was ever written ... "

Many scans of the Monthly Packet are now fully available online

in the Internet Archive.

Click

here to find the current list. (opens new tab for Internet Archive)

The Monthly

Packet online (for Gale subscribers)

Issues of the Monthly Packet of Evening Readings from 1851 to 1899

are available to subscribers to the Gale resource ‘Nineteenth Century

UK Periodicals. Part I: Women’s, Children’s, Humour, and Leisure’.

This is available via many university libraries for those who have access to them.

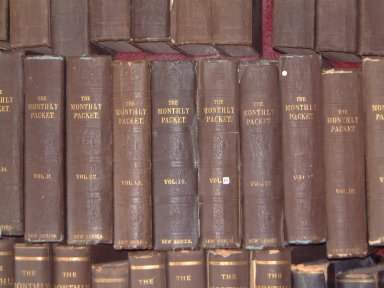

The Monthly Packet of Evening Readings for Members of the English Church

Periodical edited by Charlotte Mary Yonge from 1851 until 1893, when her younger friend Christabel Coleridge took over as editor. Publication ended in 1899.

There were four series, two of which were termed ‘New’.

The bound volumes covered six months (January–June, July–December).

Volume numbering (on spine) started afresh with each

series, but a running volume number was also maintained (usually stated

on the front title page of bound volumes).

It is also provided in the online version of the Monthly Packet. Using

these running numbers enables a volume to be uniquely identified without

needing to state the series.

| [First Series] of 30 volumes (1851–1865) on spine, 1–30 | = | (running) vols 1–30 |

| ‘New Series’, 30 volumes (1866–1880) on spine, 1–30 | = | (running) vols 31–60 |

| ‘Third Series’, 20 volumes (1881–1890) on spine, 1–20 | = | (running) vols 61–80 |

| ‘New Series’, 18 volumes (1891–1899) on spine, 1–18 | = | (running) vols 81–98 |

The list below showing (in Roman numerals) part numbers is not yet complete.

|

FIRST SERIES 1851-1865

|

Volume

|

Parts

|

Series name

|

| –– | |||

| January-June 1855 VOLUME IX XLIX-LIV First | |||

| January-June 1856 VOLUME XI LXI-LXVI First | |||

| July - December 1858 VOLUME XVI XCI-XCVI First | |||

| January-June 1859 VOLUME XVII XCVII-CII

First |

|||

| January-June 1861 VOLUME XXI CXXI-CXXVI First | |||

| January-June 1862 VOLUME XXII CXXXIII-CXXXVIII

First |

|||

| July - December 1862 VOLUME XXIV CXXXIX-CXLIV

First |

|||

| January-June 1864 VOLUME XXVII CLVII-CLXII

First |

|||

| July - December 1864 VOLUME XXVIII CLXIII-CLXVIII First | |||

|

SECOND "New" SERIES 1866 – 1880

|

Volume

|

Parts

|

Series name

|

| January-June 1866 | VOLUME I | Parts I-VI | New Series |

| July–December 1866 | Volume II | Parts VII to XII | New Series |

| January-June 1867 | VOLUME III | Parts XIII-XVIII | New Series |

| July - December 1867 | VOLUME IV | Parts XIX-XXIV | New Series |

| January–June 1868 | Volume V | Parts XXVI-XXX | New Series |

| July–December 1868 | Volume VI | Parts XXXI -XXXVI | New Series |

| January-June 1869 |

VOLUME VII | XXXVII-XLII | New Series |

| July - December 1869 |

VOLUME VIII | XLIII-XLVIII | New Series |

| January-June 1870 |

VOLUME IX | XLIX-LIV | New Series |

| July - December 1870 |

VOLUME X | LV-LX | New Series |

| January-June 1871 |

VOLUME XI | LXI-LXVI | New Series |

| July - December 1871 | VOLUME XII | LXVII-LXXII | New Series |

| January-June 1872 | VOLUME XIII | LXVIII-CII | New Series |

| January-June 1874 |

VOLUME XVII | XCVII-CII | New Series |

| July - December 1874 VOLUME XVIII CIII-CVIII

New Series |

|||

| January-June 1875 VOLUME

XIX CIX-CXIV New Series |

|||

| July - December 1875 VOLUME XX CXV-CXX

New Series |

|||

| January-June 1876 VOLUME XXI CXXI-CXXVI New Series | |||

| January-June 1878 VOLUME XXV CXLV-CL

New Series |

|||

| July - December 1878 VOLUME XXVI CLI-CLVI

New Series |

|||

| July - December 1879 VOLUME XXVIII CLXIII-CLXVIII New Series | |||

| July - December 1880 VOLUME XXX CLXXV-CLXXX New Series | |||

|

THIRD SERIES 1881-1890 |

Volume

|

Parts

|

Series name

|

| January-June 1882 VOLUME III XIII-XVIII

Third |

|||

| July - December 1882 VOLUME IV XIX-XXIV

Third |

|||

| July - December 1882 VOLUME IV XIX-XXIV

Third |

|||

| January-June 1883 VOLUME V XXV-XXX Third |

|||

| January-June 1884 VOLUME VII XXXVII-XLII

Third |

|||

| July - December 1884 VOLUME VIII XLIII-XLVIII

Third |

|||

| January-June 1885 VOLUME IX XLIX-LIV

Third |

|||

| July - December 1885 VOLUME X LV-LX

Third |

|||

| January-June 1886 VOLUME XI LXI-LXVI

Third |

|||

| July - December 1886 VOLUME XII LXVII-LXXII

Third |

|||

| January-June 1887 VOLUME XIII LXXIII-LXXVIII

Third |

|||

| July - December 1887 VOLUME XIV LXXIX-LXXXIV

Third |

|||

| January-June 1888 VOLUME XV LXXXV-XC

Third |

|||

| June – December 1888 VOLUME XVI

XCL-XCVI Third |

|||

| January-June 1889 VOLUME XVII XCVII-CII

Third |

|||

| July - December 1889 VOLUME XVIII CIII-CVIII

Third |

|||

| January-June 1890 VOLUME XIX CIX-CXIV

Third |

|||

| July - December 1890 VOLUME XX CXV-CXX Third | |||

| New Series (co-edited with Christabel Rose Coleridge) 1891-1899 |

Volume

|

Parts

|

Series name

|

| January-June 1891 VOLUME I I-VI

New Series |

|||

| July - December 1891 VOLUME II VII-XII

New Series |

|||

|

January-June 1892 VOLUME III XIII-XVIII New Series |

|||

| July - December 1892 VOLUME LXXXIV

CCCCXCVII-DII New Series – IV |

|||

| July - December 1894 VOLUME ?? DXXI-DXVI

New Series – VIII |

|||

| July - December 1897 VOLUME XCIV DLVII-DLXII

New Series – XIV |

|||

| January-June 1898 VOLUME XCV DLXIII-DLVIII

New Series – XV |

|||

| July - December 1898 VOLUME XCVI DLXIX-DLXXIV

New Series – XVII |

|||

| January-June 1899 VOLUME XCVII DLXXV-DLXXX New Series – XVII | |||

About The Monthly Packet

This article was kindly provided by Amy de Gruchy,

whose M. Phil. thesis was on The Monthly Packet

The Monthly Packet, a Victorian magazine, was founded in 1851 and ceased publication in 1899. The full title, The Monthly Packet of Evening Readings for Younger Members of the English Church, made it clear that the magazine was intended for youthful Anglicans. The Introductory Letter in Volume 1, and the correspondence of the first editor, show that it was for girls of the middle and upper classes. Later, the omission of the word "Younger" from the title and the inclusion of much material suitable for adults reveal the widening age range of the readership. Internal evidence suggests that this readership was considerably larger and more socially mixed than might have been expected from the price and number of the copies.

Aims - stated

The aims of the magazine, as stated in the Introductory Letter, were

to provide instruction, entertainment and improvement, together with reasons

for remaining loyal to the Established Church. These aims were always

fulfilled, though in differing proportions, and interpreted in different

ways.

Aims - unstated

Like other magazines, then and now, The Monthly Packet offered

a particular view of life, and encouraged certain attitudes in the readership.

Central to this view of life was the belief in the need to preserve a

largely imaginary status quo in religion, politics and society. Here God

ruled the Universe, the clergy of the Church of England ruled the laity,

the party most opposed to change ruled (or should rule) the British Isles,

landowners and employers ruled tenants and workers, husbands ruled wives,

and parents ruled children. The response required from the readership

was to uphold this status quo, and submissively accept their own position

within it. The magazine actively discouraged readers from learning other

viewpoints.

However, over the years, the magazine modified its stance. It had been founded by some of the original members of the Oxford Movement to counter what they saw as the extremism of the new wave of Anglo-Catholics. In later years, many Anglo-Catholic developments were accepted by the magazine, which also became more tolerant of Roman Catholicism and Non-Conformism. It came to recognise that certain ills in society, such as poverty and ignorance, needed to be addressed rather than accepted or ignored. There was less stress on submission and obedience in the family.

Another unstated aim was to encourage an interest in education, missionary work and charitable giving. These reflected the concerns of the first editor, and throughout her rule of over forty years, they were steadily promoted.

The first editor

The magazine's first editor was Charlotte Yonge, a devout churchwoman

who was greatly influenced by John Keble, one of the leaders of the Oxford

Movement. She was a successful authoress who combined editing The Monthly

Packet with writing novels for adults, teenage and children's fiction,

biography, history, school textbooks and much else. As well as editing

The Monthly Packet, Charlotte Yonge contributed largely to it.

She exercised tight control over the material submitted for publication,

and the magazine can be seen as an expression of her personality and beliefs.

The modern reader

For the general reader, the magazine offers an interesting picture of

Victorian life, with the changing prejudices, ideals and attitudes of

a particular religious and social group.

For the Charlotte Yonge enthusiast, there is the opportunity to read many of her works in their original context, and to gain a clearer understanding of her views.

In its articles, fiction and correspondence pages, the magazine provides much useful evidence for specialists in history, theology, education, sociology and women's studies.

Paper on The Monthly Packet by June Sturrock

"Establishing Identity: Editorial Correspondence

from the Early Years of The Monthly Packet"

Victorian Periodicals Review - Volume 39, Number 3, Fall 2006, pp. 266-279

University of Toronto Press

The Monthly Packet and Social Concern

An article by Celia Bass in

The Review of the Charlotte Mary Yonge Fellowship

This article is available in Review of the Charlotte Mary Yonge Fellowship Number 8, Winter 1998/1999

It is not yet available online.

For contents lists of all issues of the CMYF Review, with some articles online, click here

The Melanesian Mission and The Monthy Packet – extract from The Monthly Packet, with introduction by Cecilia Bass

An extract from The Monthly Packet,

with introduction by Cecilia Bass in

The Review of the Charlotte Mary Yonge Fellowship

This article is available in Review of the Charlotte Mary Yonge Fellowship Number 3, Summer 1996

It is not yet available online.

For contents lists of all issues of the CMYF Review, with some articles online, click here

CONTENTS LISTS

Contents list – New Series 1866 Number 1

A Gossip about Books 158

A New Year and a New Book 1

Answer to Kiddle 383

A Feep at a Deaconess1 Home . 572

A Twelfth-Day King 46, 123, 215, 310,416, 516

Autobiography of Prince Charles of Hesse 447

A Vision 351

Boulton and Watt 341

Cameos from English History 13,195,395, 489

Catherine de Bourbon, .268

Comparative Danish and Northumbrian Folk Lore .29,248

Correspondence 91, 188, 286, 379, 477

Early Scandinavian History 23, 98, 298

Easter at Corfu . 289

Easter-tide at Hursley 385

Eliza; a Real Portrait 560

Falling Stars 360

Hints on Beading 90, 186, 378, 579 Home for Invalid Children 180

Imagination 469

'Is the Boy a Good Boy?' 279

Letters on Geology 83, 154,258,336, 456, 566

Lilla's Relations 38,107, 224, 317, 401

Milo; or, The Dream 474

Old English Poets .496

On the Benefits of Cold Water . 182

Our Christmas Theatricals 60

Our Sick Poor 86,375

Our Ship 283

Practical Headings on the Apostles' Creed 3, 97, 193, 291, 390, 481

Poetry:-'Depart from Me.' 185

Reminiscences of North Wales 172

Riddles 287, 579

Roman the Reader 67, 130, 230

' Tarcisius, the Child Martyr' 392

The Buzzards 366

The Capture; or, The Days of the Fenians 544

The Englishman in India 6, 294

The English Family in Germany Again 325, 439, 523

The Fairford and Hursley Windows 483

The Friday Fast 281

The Grottoes of Adelsberg, and the Proteus Anguinus 459

The Loss of' The London' 577

The Six Cushions 55,118,205,305,409,509

The Three Flags; or, the Saltash Rower 421

The Way to Paradise 144

Soaps Suds Again

"Perhaps the most popular performance (of the entertainment) was a reading - 'How four men tried to keep house alone.' "

This

article appeared in the Monthly Packet of

January 1884 – pp 57-62.

It

was printed in the Review of the Charlotte

Mary Yonge Fellowship, Edition 8, Winter 1998/99

IT was Christmas Eve, 1881, in Moon Street. All day busy preparations had been going on, as load after load arrived of evergreens, cakes, pies, and oranges, and at last all were safely stowed away; decorations were finished, the last kind helper had gone away to return to the West End, and we drew our girls and lodgers together round the fire to sing and talk, and if possible keep them from the streets. Already the wild, noisy crowd was buzzing outside, and bursts of discordant laughter and snatches of horrible songs told only too plainly that the devil of drink was abroad. As early as four lock Betty Flake had staggered in half Wnk, announcing that she had an appointment which would soon take her out again. We guessed too truly what the appointment was, and Miss lay had a tussle with her to prevent her keeping the rendezvous; finally we prevailed, and the poor girl threw her shawl up on to a shelf to protect herself from the temptation to go out; then devoted herself to decorating the gaslight - a rather dangerous experiment, but we were glad of anything to keep her employed. Next came in Peggy O'Brien (my special friend), only eighteen, a three months' bride, nearly desperate over her drunken husband, and worn out with following the waits, from midnight to morning, as they went from public-house to public-house, at each of which they were 'treated', girls and men carrying out bottles of gin "to revive the spirits!" We fed poor Peggy and tried to soften her, and despite many threats to go out again, she sat on with us all through Christmas Eve. And now Betty Flake became restless and said she must have a run.

"I have some shopping to do," said Miss Tay; "will you come and take care of me?"

Betty was delighted, and when I asked her to be careful of my friend, she answered indignantly, "Do you think I'm such a brute as to let any one touch her?"

So the walk was safely accomplished, and by degrees the air, resisting evil, and the tea, brought her back to her senses; but soon another girl, Peggy number two, was our difficulty. She had promised, she said, to go with the waits at twelve o'clock. I begged and prayed her not to, and tried to show her how evil it was. She promised not to drink a drop, but go to the waits she would.

"I was offered two shillings this morning if I would drink half a quartern of gin, and I didn't. I'm sorry now I didn't! Well! I won't drink to-night, but tomorrow I just will!"

At this cheerful point we were joined by Peggy O'Brien, who was wanted to go out with her namesake "to have a drink together"; but my entreaties prevailed over my particular friend, and she became pleader in her turn, and urged Peggy number two to stay in and also to give up her party – a party described to me as "a Christmas tree and tea party in my room," but known to Peggy O'Brien as a party of girls each to bring her subscription of gin!"

"How long are you going to keep up this party?" I asked.

"Until Boxing Day." (It was to begin on Christmas Day.)

For a long time we argued, using all our eloquence. From the outer rooms came sounds of singing, and then a message, "You are wanted." There stood a detective we had sent for about some missing blankets, and to whom we had complained of the annoyance we were put to by men and boys dashing against the door, bursting in upon us, and greeting us with vile language. I told him that the last few nights we had been left in peace.

"That's right, ma'am," said he. "I went straight to the inspector, and he's having you watched; but I have come to ask you a favour." And he brought in a young Frenchwoman who had been turned out of her lodgings this Christmas Eve, and her box kept from her, merely because the room was wanted for some one else. She had neither money nor friends; her last ten shillings had been spent on her rent, and no magistrate would be sitting until Monday. We gladly welcomed her, she was very quiet and pleasant, and said she was much happier with us. Then I returned to my back-room fight, and won it at last; the wicked tea party was put off, and Peggy closed the contest with this remark – "I wish I had taken that gin and the two shillings this morning!"

The evening wore on, and we barred the door and went up to sleep as best we might, with the dancing and singing in the streets, which was still going on when we awoke. For Christmas greeting we had the wild, drunken sounds in the street, and songs to which we tried to close our ears. The first to come in was our little maid Susan, who sleeps at home and comes over early. She had promised not to go to the waits, and we had handed her over to her father on Christmas Eve, begging him to take care of her. Instead of doing so, he took her to her drunken sister, became drunk himself, and they kept her out until three in the morning. Poor child, she appeared this morning very tired and unhappy, and told us she had thrown away the gin forced upon her. Good little maid! how busy she was, doing her best to please us, and make us all comfortable.

After one short hour of blessed peace at the early service we returned to the noise without, and bustle within, of Moon Street. We labelled presents for lodgers, arranged for the grand Christmas dinner, and then we took the lodgers and girls to church. How they enjoyed the dinner which followed! And a funny company we were - lodgers and washerwomen, girls and ladies, mission women and little maids. Interruptions of course there were; girls to buy tickets for the evening's tea and entertainment; Betty Flake came to sit with us, and be kept from temptation; a present of tea and cakes 'for the ladies,' and many a 'Happy Christmas,' from fellow-workers who were beginning to arrive. It was now time to distribute the presents, and as soon as each shawl was given it was instantly donned by the owner. One woman was not pleased, and growled out,

"This for me? I as 'as lived in noblemen's families! Give me noblemen and their ways, says I!"

At five o'clock the girls were crowding the door, and ticket-taking began. Peggy O'Brien was among the number, all clean and dressed, but alas! having had some drink. Tea was a funny meal. The girls think we give them a very good meal for fourpence - a big bun, two lumps of cake, bread and butter, and as much tea as they can drink. When the merry meal was over, and the fragments cleared away, we arranged the forms in rows, and our lady and gentlemen helpers began a concert; but it was 'no go at all.'

'Sing something that we can sing,' shouted Irish Polly.

So we sang songs with choruses, but there was a tendency to 'naughty songs, and we were obliged to give way to the desire to dance; and say what people will, dancing seems to let out the devil, as it were, and to save them from their wild moods. There was a cry of delight when the dance was announced. The rooms were cleared and the harmonium brought to the fore, and the room seemed to move as the dancers waltzed round and round in perfect time, and with intense enjoyment. But presently the two Peggys and Betty became restive; the taint of drink was on them and they could not be controlled. 'Let us out, and we will come back in ten minutes all right,' said they. There was no help for it; all we could say was in vain. They did return, but, alas! their guilty faces and manners told their own tale. After that Mr. Hoffman kept the door, and locked it each time after he admitted some new comer; but all the evening the Peggys, Betty, and a fourth, Jeannie Carter, tried to dodge us and to effect their escape. The only peaceful hour was that when every eye was fixed on the conjurer and his magical deeds. These over, we had more tea and more dancing, but Peggy O'Brien could not be quieted; so I carried her off to my room up stairs to show her my Christmas cards, and to implore her not to go out again to drink. I knew how hard a thing I was asking, for the girls have often told us that water does not quench the thirst of those who have once given way to drinking spirits, and Peggy's mother was an habitual drunkard, and this day her husband was also drunk. No words had any effect on her until I put it on personal grounds, and asked, 'Well, Peggy, which is it to be? Gin or me?' Then she put her arms round my waist and in a very soft voice she answered, 'You'. Then she set to work to tidy our room, to boil the kettle and to prepare tea for the weary workers; the devil was conquered this time to return again to the fight shortly afterwards.

The girls stayed with us pretty quietly until eleven, and we knew, to our joy, that at that hour on Sundays and Christmas Day the public-houses were closed. Christmas Day was over.

Sunday followed, with its churchgoing, dinners, and sundry people's bad tempers after Christmas rioting. Though there was fortunately very little of the public-house, people knew how to meet the difficulty, and had stocked their rooms with drink and company. Poor Peggy! She came in at dinner-time very much the worse for drink, with her sister's fat baby in her arms. The baby was in imminent peril: its head was banged against the floor! I seized it; but Peggy held tight by the legs until I boxed her ears, locked her up, and so kept her by force from going out. By tea-time she was quieter, and helped us to label presents for the next day. She said to me in the evening, 'I wonder 'owever you've kep' me in: my people couldn't 'ave done it! and if you 'adn't I'd 'ave been rolling drunk about the street about this time, and in the lock-up next.'

We had a large number of girls from 7 pm to 10 pm singing hymns and listening to the story of St. Stephen and the bravery of saying 'no'.

We kept the poor tempted young things until eleven o'clock had struck, and then the third day was over.

Boxing Day began damp and weary. Mummers stood outside the gin-shops and crowds round them drinking. From the window we saw Peggy and called her to come in, which she reluctantly did, and was kept safe. One room full of girls helped to sweep, carry, and scrub, and all the while the noisy crowd drank and roamed the streets.

Dinner-selling over in our coffee-shop, and shutters up, we made our tea-preparations, and packed up refreshments and stores to send across to the Vestry Hall for sale during our evening entertainment. Then sixty girls sat down to tea, which, of course, was followed by dancing until Lady G. White distributed the prizes. So the evening passed until eight o'clock, when we all adjourned to the large room over the way, lent us by the parish guardians. The entertainment was a great success. Besides our girls, 150 older laundresses and their husbands attended, and the interest and attention never flagged until past midnight,when the last song was sung and the doors closed. Perhaps the most popular performance was a reading – 'How four men tried to keep house alone.' When it came to their ironing their own shirts the interest was intense. The company held their breath as the story told how the red-hot iron went down on the best shirt front, and thrilled as they 'seemed to see the awful 'oles it made.'

I found Peggy O'Brien and her husband in the refreshment department. He was told to behave himself to me, and he did; but I heard afterwards that he had tried to pawn his wife's new petticoat She told me she should be safe from temptation, if we would keep on the entertainment until twelve o'clock. As I said, we broke up a few minutes after, and going home I asked our little maid, 'The worst is over now, isn't it?' 'Oh, no; the pawnshops is open to-morrow, and they'll drink till they have pawned everythink.'

A Tangled Tale

Not strictly Yonge, but a work which first made its appearance in The Monthly Packet.

From Lewis Carroll's December 1885 Preface to the collected edition, published in 1885:

"This Tale originally appeared as a serial in The Monthly Packet beginning in April 1880. The writer's intention was to embody in each Knot (like medicine so dexterously, but ineffectually, concealed in the jam of our early childhood) one or more mathematical questions – in Arithmetic, Algebra, or Geometry, as the case might be – for the amusement, and possible edification, of the fair readers of that magazine."

Tangled Tale is also available as a free audio book from Librivox

Click here for the Librivox page for

A Tangled Tale (again)

From a bookseller's notice

Lewis Carroll Arthur B. Frost A TANGLED TALE

Carroll, Lewis [pseudonym of Charles

L. Dodgson]. A TANGLED TALE.

With Six Illustrations by Arthur B. Frost.

London: Macmillan and Co., 1885.

First Edition, which consisted of only 1000 copies (there was also a second printing with "Second Thousand" added to the title page, a third with "Third Thousand," etc.).

A TANGLED TALE consists of ten "knots," tales in which are embedded mathematical puzzles. For example, a tale sited at the Chelsea Pensioners' Hospital ends with this puzzle: if 70% of the pensioners have lost an eye, 75% have lost an ear, 80% have lost an arm, and 85% have lost a leg, then what percentage, at least, must have lost all four?

The "knots" originally appeared in the "Monthly Packet," a magazine edited by Charlotte Yonge that was read chiefly by ladies. This volume includes, at the rear, Carroll's solutions to the puzzles, together with his discussion of some of the solutions submitted by readers of the "Monthly Packet." (The dedication verse is also a puzzle: the dedicatee is Edith Rix, using the second letter in each line.)